Grief, Greeting Cards, and Saying the Right Thing

Grief is a deeply personal experience, yet one that so many of us will face. For young adults, navigating loss can be especially isolating, with few support systems or resources tailored to their needs.

In this special Q&A, we speak with Rachel from Love Loss Discoballs, who shares her own journey through grief and why meaningful connection—whether through conversation, community, or even a well-designed greeting card—can make all the difference.

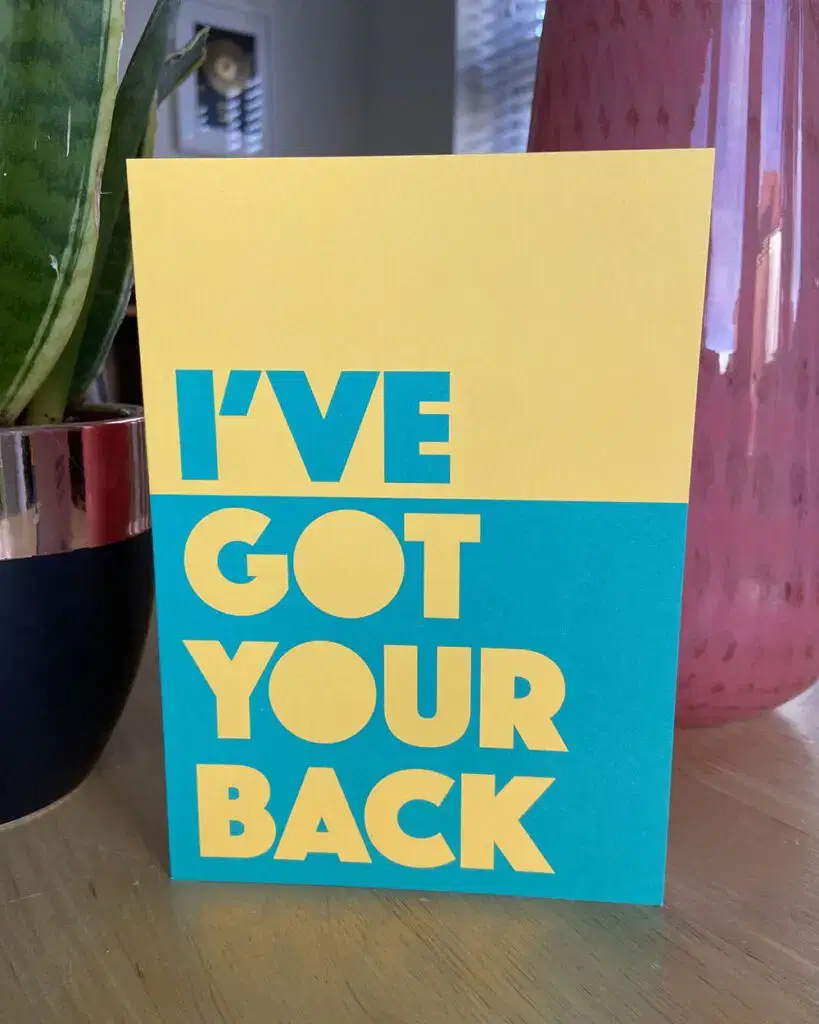

Rachel’s Liverpool based business, Love Loss Discoballs, is on a mission to bring colour and light to the world of sympathy and support. Rachel and Warren Hart-Phillips have designed a collection of modern greetings cards that speak openly and colourfully to the real experiences of loss, struggle, and support, all born from their own experiences of grief and healing,

From the challenges of losing a parent young to the evolving ways different generations approach sympathy, Rachel offers thoughtful insights into how we can better support those who are grieving.

General Grief & Young Adults

Q .Losing a parent at a young age is something many people aren’t prepared for. What did you find most difficult about grief in your early 20s?

Rachel: One of the main things I found tough was feeling so different to my peers – and it’s at a stage in your life where that’s quite important for you. I remember not wanting to feel pitied by my friends, particularly the new ones I had just made at university. It can be incredibly lonely when you feel as though no one else around you can relate to your situation – and there wasn’t much support available for grieving young people like there is now.

Q. How did receiving (or not receiving) sympathy cards impact your experience of grief?

I don’t remember receiving one to be honest. I was always added on to the ones which were given to my mum, which of course didn’t speak to me at all – and this was very isolating. It made me feel that somehow my grief wasn’t seen – and it felt like a sad reminder that I was too young to be losing a parent, as cards simply didn’t exist for my situation.

Q: What do you think people get right—and wrong—when trying to support a grieving young adult?

A lot of people told me that I was ‘so strong’ after I lost my dad, and I think that was very dangerous at that age. It’s so important to teach young grievers that their emotions are valid, and they are allowed to process their grief in whatever way is right for them – they don’t need to feel pressure to be ‘strong’.

One of the standout memories for me was how affected my best friend was by my dad’s death. I remember seeing her sobbing looking at his photograph at his funeral and finding it quite comforting to see her so emotional. I think it can be easy to try to not show emotions in front of young people for fear of upsetting them, but it really does help to validate how they are feeling, to see others being so open in their grief.

Q. Designing the perfect sympathy card for someone in their late teens or early 20s could be really challenging for some publishers/designers, do you have any advice?

Grief is so deeply personal – and design is so subjective – so it is certainly a challenge to get it ‘right.’ I think that keeping it simple is key. Colour is so important – and again it’s about striking a balance between using uplifting colours but not being too bright.

In terms of language – we work on the basis that if it’s not something you would say to someone’s face then we don’t put it on a card. Platitudes like ‘With deepest sympathy’ feel so out of date and would be meaningless to a young person. Supportive messages of friendship work well, along with not being afraid to be specific about the loss, to make the person feel that their pain is acknowledged.

Q. Why do you think greeting cards for younger people experiencing loss are so rare?

Grief is often still seen as something that primarily affects adults. Many traditional sympathy cards are designed with older recipients in mind – either addressing the loss of an elderly relative or using formal language that doesn’t always resonate with younger people.

There’s also a hesitation around talking to young people about grief in general. People worry about saying the wrong thing, so sometimes they say nothing at all. That silence can be isolating for a young person going through loss. A card designed specifically for them – one that acknowledges their pain in a way that feels relatable and not overly heavy really could make all the difference.

Q: Do you think there’s a difference in how younger and older generations approach sympathy and grief?

Yes, I think there’s a big difference. Older generations often grew up in a time when grief was more private, and this ‘stiff upper lip’ mentality is still prevalent – both in grief and any kind of mental health struggles. Sympathy was usually expressed through formal gestures, like sending a traditional card or attending a funeral, but beyond that, grief wasn’t always openly discussed.

Millennials and Gen Z, tend to be a lot more open about grief. They’re more likely to talk about it online, share personal experiences, and seek support in less traditional ways. They also appreciate more direct, authentic communication – rather than formal, scripted sympathy messages, they want something real, something that acknowledges the messy, unpredictable nature of grief – whilst honouring the loved ones who have been lost.

Men & Suicide Loss

Q. The loss of a loved one to suicide is deeply complex and often comes with added layers of guilt or unanswered questions. How did you navigate this type of grief?

Losing my first husband to suicide was unlike any other grief I had experienced. There were so many layers to it – shock, sadness, guilt, anger, confusion, even shame. It wasn’t just about missing him; it was about trying to make sense of something that felt impossible to understand.

In the early days, I think I just survived. I focused on getting through each hour and each day. I was pregnant at the time, which gave me something to hold onto – I had to keep going for my baby.

What helped me most was finding safe spaces where I could be honest about what I was feeling – seeking out others with the same experiences online, in support groups, or even in my writing. I had to learn to let go of the idea that I would ever have all the answers. Instead, I tried to make peace with the fact that I could go on to live my life and honour my husband, while also accepting that his death wasn’t my fault.

Q: Many men struggle to express emotions or seek support. Do you think greeting cards could play a role in changing this?

Yes, I really do. Men are often conditioned from a young age to be ‘strong’ and to suppress their emotions. There’s still a stigma around men openly expressing vulnerability or asking for support, and that can make mental health struggles feel even more isolating.

Greeting cards might seem like a small thing, but as we all know they can be a powerful tool in breaking down those barriers. A card gives someone permission to say something they might struggle to say out loud, and it feels less intrusive than a phone call or a visit.

It’s a huge change in the narrative – and we’ve not sold many cards to men at all just yet. A man is unlikely to go online specifically to buy a card for a mate but we’re trying to be creative with ideas about where we could make them available.

Q: What kind of messages do you think we need to see more on greeting cards to make them more inclusive and supportive?

Again, it all comes down to simplicity in both words and design. Words like ‘Here for you mate’ or ‘I’ve got your back’ feel relevant and are the kinds of phrases people would actually say to each other. There really isn’t much more to say on the inside of the card either, that short sentence could be everything that’s needed.

Q: There’s often stigma or discomfort around talking about suicide. How can a simple card help break that silence?

I think in two ways – for someone who is struggling with their mental health, a supportive message could remind them that they are loved and that they matter. A card displayed on a windowsill or a mantlepiece would be a constant reminder of this – and unlike a text message it doesn’t get lost.

For suicide loss, people just don’t know what to say. People worry about saying the wrong thing, so sometimes they say nothing at all – which can leave those grieving feeling even more isolated.

A card can acknowledge the loss in a way that feels tangible. It doesn’t have to be full of grand words; even something as simple as “There are no words” can mean everything to someone struggling with grief after suicide. It reassures them that they aren’t being avoided or forgotten, that their loss is real and valid, and that they don’t have to carry it alone.

Breaking the silence doesn’t mean having all the answers – it just means showing up. A card is a small but powerful way to do that.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who wants to send a card but is worried about saying the wrong thing?

Don’t let the fear of saying the wrong thing stop you from saying something. Silence can feel incredibly isolating for someone who is grieving, and even the simplest message can be a huge comfort.

If you’re unsure what to write, keep it honest, heartfelt, and simple. You don’t have to come up with the perfect words or try to ‘fix’ anything. Trying to make someone feel better by saying something like ‘at least they’re out of pain’ is possibly one of the worst things you can say to someone during grief, even though it’s said with the best of intentions.

Grief isn’t something that can be fixed, and all someone needs is for someone to acknowledge their pain. Focus on letting them know you care and you’re there for them – that’s the most comforting thing of all to hear when you’re grieving.

Q. What are some small but meaningful ways friends can support each other through grief?

Sometimes the smallest gestures can mean the most when someone is grieving, here are some of my top suggestions which helped me during my darkest times:

Rachel’s Advice for supporting a friend with grief

Further Information

Grief can be overwhelming, and no one should have to navigate it alone. If you or someone you know is struggling, there are incredible organisations that can offer support: